The classic tale of “the rich getting richer while the poor get poorer” never seems to get old. The newly released Takers Not Makers report from Oxfam fuels the idea that billionaire wealth is skyrocketing while the poor are getting poorer. They claim that poverty levels have barely changed since 1990, and that 60 percent of billionaire wealth is “taken,” not earned, arguing that the richest must bear the cost of “economic justice” through various means including heavy taxation. The argument is nothing new — it is based on the zero-sum fallacy, which assumes that one person’s wealth must come at the expense of another’s, ignoring the reality that economic growth expands wealth for everyone.

Despite the popular belief that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, this claim is not only economically misguided but factually incorrect. Using data from The Mercatus Center’s working paper Income Inequality in the United States, we can demonstrate how flaws in inequality data often exaggerate the problem, explore why the claim that the poor are getting poorer is inaccurate, highlight why shaping policies around resentment and envy of the rich does more harm than good, and why the real solution lies in addressing the root causes of inequality through private-sector opportunities rather than government intervention.

Understanding Inequality Data: The Measurement Problem and What’s Left Out

The first item you should be mindful of when studying income inequality is that studies often exaggerate disparities due to flawed measurement methods. The two main data sources — tax records and household surveys — both have limitations. Tax records accurately capture high earners but miss low-income individuals who do not file taxes, while household surveys underreport high earners’ actual income, distorting inequality estimates. Additionally, many studies ignore government transfers like Social Security, Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and more, which reduce inequality significantly. Readers should be mindful of these measurement problems and government transfers to avoid being misled by incomplete or exaggerated inequality narratives.

Another flaw in inequality studies is ignoring non-wage compensation, such as health insurance, retirement benefits, and bonuses. This is particularly important because nonwage compensation has increased substantially since 1950, growing from just 5 percent to nearly 20 percent of total employee compensation. Since many lower-income workers receive much of their earnings in benefits rather than wages, leaving these out overlooks the financial support and economic well-being these benefits provide. Additionally, when factoring in government benefits like Social Security, Medicaid, and tax credits, the measured income gap shrinks by about 11 percentage points. Redistribution significantly reduces inequality, at least in the short term. If nonwage compensation and government benefits were factored into inequality studies, the measured gap would likely shrink even further, providing a fuller and more accurate picture of income distribution.

Debunking the Myth: Why It’s Factually Incorrect to Say the Poor Are Getting Poorer

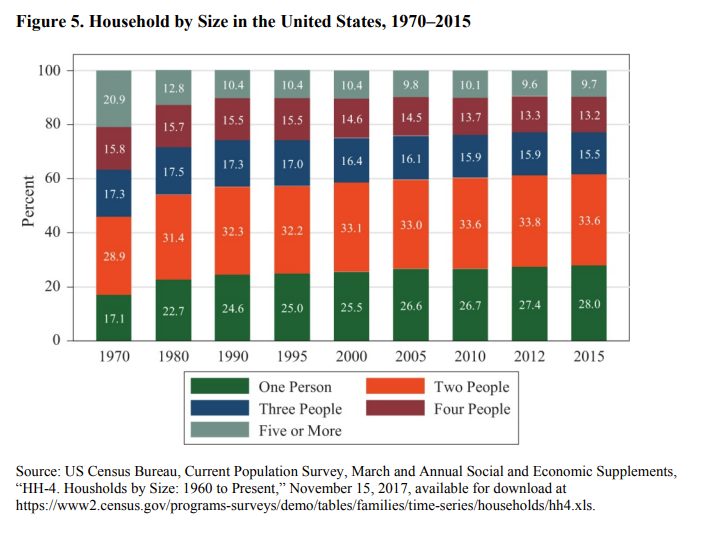

A major reason why income inequality appears to have increased is not just that the rich are earning more, but because of significant cultural shifts in household size and marriage patterns, which affect how inequality is measured. In the past, larger households with multiple earners helped balance income differences, while today, fewer people are getting married, more people live alone, and single-parent households have increased. As a result, more households rely on a single income instead of combining earnings, making household income appear lower even if individual wages have remained stable, as shown in Figure 5: Household by Size in the US (1970–2015).

Additionally, high-income earners are increasingly marrying each other (a trend known as assortative mating), while lower-income individuals are more likely to remain single or marry others with lower earnings. This concentrates wealth within high-earning couples and makes household-level inequality seem larger than it actually is. If household size is one of the primary ways we measure inequality, then naturally, the data will make it look like inequality has skyrocketed, when in reality, changes in household structure are being reflected. It’s not always as simple as saying “the rich are just earning more.” To truly understand inequality, we have to look at how the data is measured and what societal changes are influencing those numbers, rather than assuming the gap between rich and poor is growing purely because of differences in wages.

This brings us to one of the biggest factors that is driving the wage gap -education and skill levels. As seen in Figure 9, wage distributions among workers (Logarithmic), 1980 vs. 2016 show that while wages increased for all workers, the highest earners saw much larger gains. The right side of the wage distribution curve (representing high earners) shifted significantly in 2016, highlighting that top earners experienced far greater wage growth than lower earners. Even among workers with lower education levels, wages still increased, but not nearly as much as for those with advanced degrees and specialized skills. This reinforces that education and skill level — not just income disparities — are major drivers of inequality, as high-skilled workers are rewarded in today’s economy, while lower-skilled jobs have become less valuable.

The Income Inequality in the United States paper by Mercatus provides clear evidence that both the rich and the poor are getting richer, but at different rates, making it essential to understand why this is happening in the broader income inequality debate. As the demand for high-skilled labor has grown, college graduates and specialized workers have experienced significantly greater wage growth than those without degrees. This proves that income inequality has widened not because the poor are earning less, but rather that high earners are accumulating wealth at a faster pace due to the increasing returns on education and specialized skills. Instead of asking how we can take from the rich to give to the poor, the more important question is how we can accelerate income growth for lower earners to reflect the faster gains seen at the top, which we will explore next.

Punishing the Wealthy Won’t Fix Inequality — Expanding Economic Opportunity Will

If education and skill level are the main drivers of income inequality, then the solution should focus on expanding opportunities rather than punishing success through forced redistribution. The “rich getting richer while the poor get poorer” narrative, fueled by reports like Takers Not Makers, oversimplifies inequality and promotes resentment-based policies rather than real solutions. As the Mercatus working paper shows, inequality is often misrepresented, with high earners seeing faster wage growth due to education and skill differences — not because the poor are getting poorer. Policies that vilify high earners through heavy taxation and redistribution fail to address the root causes of inequality and often do more harm than good.

The real solution lies in private-sector opportunities rather than government intervention. A free-market approach to economic mobility emphasizes developing skills and education without government dependence because self-sufficiency, not redistribution, leads to lasting prosperity. Government programs create dependency, while market-driven solutions empower individuals to increase their earning potential through opportunity and effort. While businesses, charities, and trade schools already offer education and workforce development, the cost of expanding these programs remains a barrier. Creating the right incentives — such as reducing regulatory burdens and tax incentives — makes it easier and more cost-effective for businesses to expand skill-based training and tuition assistance programs. Instead of focusing on redistribution, we must prioritize policies that encourage private investment in workforce development, giving low earners the tools to gain skills, move up the income ladder, and narrow the inequality gap.

Inequality isn’t about preventing the rich from getting richer — it’s about ensuring that all workers, regardless of income level, have the opportunity to thrive. When policies are shaped by resentment rather than opportunity, they hinder progress instead of helping those in need. Instead of focusing on higher taxation and government redistribution, the priority should be on empowering individuals to gain the skills necessary to compete in a changing economy. The goal is not to tear down the wealthy, but to lift up those at the bottom by fostering a system that rewards hard work, skill-building, and economic opportunity for all.